Today, March 29, is Mike’s birthday and in his honor we are posting

a previously unpublished essay he wrote in the summer of 2017.

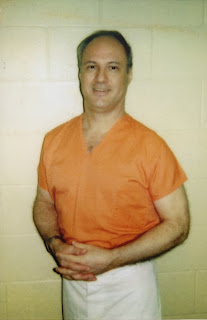

By Michael Lambrix

To read Part 8 click here

As I stood at the back of the cell one late September morning in 1988, an unfamiliar voice yelled out from somewhere downstairs, “Fire in the hole!” It was quickly echoed by others to make sure everybody heard. A white shirt was on the wing. Back then the wing sergeants and officers generally left us alone to do our own time, just as long as we didn’t make them look bad. And we’d get a heads up if the confinement lieutenant (”white shirt”) came on the wing so we could tighten up and at least make it look good. There’s a lot of truth to what they say about how shit runs downhill… — if we made the wing Sergeant look bad, it would come down hard and heavy on us and nobody wanted that.

Quickly, I tried to do what I had to do. I was already on disciplinary confinement (”the hole”) for fighting on the recreation yard a few weeks earlier over a stupid call during a basketball game. I only had about another week to do before my 30 days were up. But if I got caught with any contraband while in the hole, it would add another 15 days. Football season had already started, and I really wanted my TV back.

When they first called out, I had just started to heat up a cup of water to make my morning coffee. That isn’t as easy as it might sound when you’re in the hole. Just getting someone to smuggle a bit of instant coffee to you was enough to make you think seriously about quitting, but I loved my coffee. It was one of the very few pleasures that I had no intention of giving up if I didn’t absolutely have to. I was willing to risk another 15 days in the hole rather than do without.

Then there was the problem of heating the coffee, as there was no electricity to the cell and no coffee pot, either. Never underestimate how resourceful a prisoner can be. Each morning we got a half pint of milk at breakfast, in a small waxed carton. By taking my roll of toilet paper and wrapping it around my fingers and palm until it made a small but loosely wrapped roll, then tucking in both the top and bottom, I made what we called a “bomb.” I had purchased a small piece of wire with trading stamps. By touching the wire to the top and side of the battery while holding the end of a cotton Q-tip to the wire, first a bit of smoke, then a small flame would appear. In a single, fluid motion I would drop the battery and hold that now smoldering Q-tip to the bottom of the bomb and use it to set it on fire. The flames sprang to life in the hollow core of the bomb. I sat it down on the edge of the toilet, balanced precariously above the water only inches away. I would hold the small milk carton filled with water above the bomb, which was by now burning like a small campfire. Within minutes the water would come to a boil.

I stood there wearing nothing but my baggy state issue white boxer shorts, since even late September in a concrete and steel box gets hot, too hot to wear clothes if you don’t need to. Like most on the third floor (heat rises to the top), I wore as little as possible. When the “Fire in the hole” call came, I at first thought little of it as the daily rounds typically never had the Lieutenant coming up to the third floor. Nobody wanted to walk into the scorching oven if they didn’t have to.

But then I heard the distinctive sound of heavy brass keys turning the lock on the steel security gate leading onto the tier where I was housed. I knew they were on my floor. As quickly as I could, I pushed the burning toilet paper bomb into the toilet, a generous puff of smoke rising as the water extinguished the flame. I pushed the chromed button, causing the toilet to come to life with a loud groan flushing the disintegrating bomb down the pipes. I went to the nearby bunk, stashing my coffee under the pillow and turning a half step around to sit on the steel footlocker against the wall as if I was doing nothing at all.

No sooner did I sit down then Lt. Walmsley and the Administrative Sergeant Timothy Giebreg were standing at my cell door. Lt Walmsley called out, “Inmate Lambrix.” I had to suppress a laugh, since he obviously knew who I was, and he ordered me to stand. I stood and stepped the short step to the cell front and said, “Yeah?” He instructed me to grab my address book and get dressed as I had to go up front.

Instantly, I knew what it was. We have all seen this play out too many times before. When a white shirt shows up at your cell and tells you to grab your address book, that meant the Governor had signed your death warrant, scheduling your execution. You would be escorted up front to see the Warden. We all knew the routine.

They waited at my cell front, watching closely as I opened up my footlocker to retrieve a small notebook I had already prepared with the names and phone numbers of my family and friends. Although death row prisoners were not allowed to make phone calls, the exception was when the governor signed your death warrant they would allow you to make one phone call to either family or a friend (many of those on the row had long been alienated from their family), which is why they told us to grab our address books, I reached for my blue state issue canvas pants and apricot colored t- shirt, the color of the t-shirt indicating that I was death sentenced.

As I began to dress, a few of the guys in the hole with me called to me. They already knew what was going on, each calling out, “take it easy, Mike” and other cordial comments. A few cells away, Ted Bundy called down, jokingly telling me he’d hold my cell as long as he could. I laughed and responded that he’d better or he wouldn’t get the fruit pie I still owed him. I didn’t really owe him one but that was his weakness, he really loved his Little Hostess pies we could buy once a week off the prison canteen (store) and there never were but a few available each week so the inmate canteen clerk usually charged a premium, especially if you wanted more than one. When I could, I’d pick up a few for Ted so that he didn’t get robbed too badly by the greedy bastards out to exploit us.

Once dressed, I already knew to back up to the cell door. A I did, I felt the handcuffs being secured on my wrists. Anytime we were removed from our cell, even if only going to the shower at the front of each tier, we were handcuffed behind our back. We would stay physically restrained until we were securely locked in a cage, whether it was our assigned cell, or the shower cell, with the exception of the recreation yard and the visiting park (for social visits with family and friends).

I had only been under a sentence of death a little over four years and had not had the opportunity to pursue collateral, post conviction review. This was the only opportunity to argue evidence the jury never heard, evidence that supported your innocence. Also other substantive claims that would show that your court appointed trial lawyer failed to provide competent legal representation, resulting in a wrongful conviction.

I didn’t even have a lawyer assigned to my case. Florida’s governor, Robert Martinez, one of a then new breed of Rabid Rednecks Republicans (”RRR,” the natural evolution of the politically unpopular ‘KKK’) who won political office on promises of exploiting executions by any means necessary had, for the first time, used the power of the governors office to sign so many death warrants that it overwhelmed the judicial system. Eventually, significant changes were made to prevent future governors from abusing the power of the office as Governor Martinez had.

As I was being escorted off the tier, past each cells and barely aware of the words of encouragement spoken by each prisoner, I felt emotionally numb. The reality that I was being led to “death watch” to face my own execution, began to weigh heavily upon me.

We exited the wing, into the main corridor that runs the length of the prison (please read, Alcatraz of the South, Part I and II) the Lieutenant radioed for a security lockdown, since protocol was that anytime a “death watch” inmate was brought out into the main corridor, the entire prison was put on lockdown. Before the Lieutenant had finished broadcasting over the hand held security radio, the solid steel doors at each of the twelve wings began to slam shut, loudly echoing as steel met steel with a thunderous force. When the last door was secure we began to move up the main corridor, southward towards the “Colonel’s office,” where the Warden would be waiting.

With the Admin Sergeant to one side and the Lieutenant at the other, we moved at a leisurely pace, neither in too much of a hurry. Once past the “Corridor E” security gate, we slowly walked past the dayrooms used for general population prisoners, each dayroom separated from the main corridor by windows. At each window, prisoners looked out. Many were former death row prisoners and as I recognized a familiar face, I nodded and he would silently nod back. At almost a quarter mile long, it took a few minutes before we finally reached what is commonly known as “Times Square”, where just inside another set of security gates the main corridor intersected with the secondary hallways.

The main control room for the prison was at the southeast corner of Times Square. The officer inside electronically opened the security gate and we walked through and across the intersection another or so paces, before stopping at yet another electronically controlled security gate that led into a small complex of administrative offices as well as the small rooms where death row had their legal visits. Walking inside, we then crossed the open area at the center of these offices, going directly to the office in the far corner. I had never been in that office before, but knew it was the Colonels’. The highest-ranking security officer at each state prison, formally titled, “Chief Security Officer,” wears the quasi-military rank of Colonel.

Nudging me by the arm, the Lieutenant guided me a few steps into that wood paneled office until I stood in front of a heavy wood desk. Rumor had it that the desk was made out of the same hardwood oak used by inmate labor to build “Old Sparky,” Florida’s infamous three legged electric chair.

I immediately recognized Warden Tom Barton sitting behind the desk. He looked up at me and said, “Morning Michael…do you know why you are here?” Hearing him call me by my first name kind of threw me for a moment as I’ve known Warden Barton for a few years, and never heard him call anyone anything but inmate, usually with an unmistakable tone of contempt in his voice, comparable to the inflection a plantation owner would use towards his slaves.

As he spoke, he held up a single piece of paper that had a distinctive black border around the edge. The “death warrant” that Governor Martinez had signed, ordering my execution. Warden Barton then proceeded to read the warrant, word for word, and as he came to the end where it said that my execution was to be carried out the last week of November, at a specific day and time set by the Warden, Mr. Barton looked up over his steel framed glasses and without even a hint of emotion, informed me that I was scheduled for November 30, 1988 at 7:00 am.

Warden Barton asked if I had any questions, but I had none. As he rose to his feet, he informed me that the death watch Sergeant would explain how things work down there. I felt a hand take me by my elbow and lead me back out and down that long corridor again, only this time we did not stop at the death row housing wing that I had come off of, but instead proceeded to the very end of the corridor and the heavy steel door over which was the letter “Q”… the infamous “Q-Wing, and it wouldn’t be my last time there. I already knew that the top row of the three floors were used to house prisoners in ultra maximum security cells unlike anything else in the Florida prison system, since I had previously spent time in those cells when I got into trouble. Each of the two upper floors had twelve cells, six to each side, each cell within it’s own concrete crypt. When the steel door closed it became a world of its own, completely isolating the occupant from all else.

But this time I wasn’t brought upstairs. Instead, as we walked on to Q-Wing, I was instructed to go down the staircase inside the door. Lt. Walmsley held me by the elbow, not so much to offer support so I wouldn’t fall, but to exert his control over me. We descended downward one floor, and as we reached the bottom I was immediately surprised by how clean it was — even the concrete floor common in prison was tiled and polished to a bright shine.

To the right was a heavy steel gate made of the same bars as our cells and just inside was a Sergeant. He quickly got up from his desk and using the heavy brass key, opened the security gate and we stepped inside. I already knew the Sergeant since he worked the death row wing from time to time and we exchanged greetings. Just as I started to walk through the open gate, Sgt. D. laughed and told me I wasn’t going in there yet, pointing to the other side of the wing. I would be on the West side for now.

Locking the security gate behind him, Sgt. D. and Lt. Walmsley led me about 25 feet to the West side and then another almost identical heavy security gate was opened and we stepped inside. I had never been in this part of the prison. I walked past a small closet, a shower cell, then three cells in a row, each surprisingly large — almost twice as big as the regular death row cells.

Sgt. D. asked me which of the three cells I wanted. I laughed at the thought that I had a choice, since I’ve never been given that kind of choice before. In the open area outside the cells near a large steel-barred window was a small table with a microwave and large coffee urn on it. I said that I’d take the middle cell, not only to be close to that table, but to be as far away as possible from both the front security gate we just walked in, and the nearby solid steel door at the back. I already knew without being told that it led into the execution chamber where the electric chair awaited it’s next victim.

As soon as I was secured in the “death watch” cell, the Sergeant removing the handcuffs, Lt. Walmsley walked away without another word. Sgt. D. told me that he was going to wait a bit before he explained how things work on death watch, since I had a neighbor coming. He asked me if I wanted a cup of coffee, and I said, “Oh, hell, yeah!” Sgt. D. disappeared around to the other side of the wing where his desk was, returning a few minutes later with a small Styrofoam cup of fresh, percolated coffee which I thanked him for as I took it from him. We heard voices coming down the stairs.

A moment later Lt. Long appeared in front of my cell, escorting Amos King. He asked Sgt. D. which cell he wanted King in, and Sgt. D. said that he could pick and Amos chose the third cell and stepped inside, and once he was secured in that cell, Lt. Long left.

I didn’t really know Amos although I had met him a few times out on the recreation yard. Sgt. D. left because Amos wanted a cup of coffee, too. Because of the way the cells were situated I couldn’t see into the adjacent cells, but Amos and I began to talk around the concrete wall that separated us. The first thing we both wanted to know was how long it would be before they brought our personal property to us so that we could write our family and friends to let them know we had our death warrants signed.

As Amos and I were talking, Sgt. D. brought him his cup of coffee and then Lt. Walmsley suddenly reappeared, this time escorting Robert “Bob” Teffeteller. I had already known Bob for a few years and was almost glad to see him, since I couldn’t ask for a better guy to have to go through death watch with. Like myself, Bob had a healthy, if a bit twisted, sense of humor and didn’t waste anytime throwing his first shot at me, even before they put him in the front cell. ”Awwhh, hell, Mike,” he said in his backwoods Tennessean accent, “What the hell did you get us into now?” We all laughed, and Amos quickly quipped, “Hey don’t blame Mike, it was one of you Bob’s that done this shit,” (referring to Governor “Bob” Martinez), and we all laughed again.

As we had our little bit of fun, Sgt. D. pulled up a chair in front of my cell so he could talk to all three of us at once. With a grin, he said, “Alright, children, settle down” and we found that funny, too. Then Sgt. D. proceeded to explain the death watch protocol, letting us know that as long as we had money in our account we could buy whatever we wanted from the prison canteen everyday (instead of only once a week on the regular death row) and that there was a small refrigerator for sandwiches and sodas, and a microwave for heating things up, as well as a coffee pot just for death watch.

He then explained that we would be allowed a legal phone call once a day as well as two social phone calls to family or friends each week. Amos quickly asked, “What’s a phone?” since regular death row was not allowed phone calls, and that got a few chuckles. We would not be allowed to go to the rec yard while on death watch, and would only be allowed non-contact visits with those on our approved visiting list. We already knew all of that, since although this was our first time on death watch, we knew from others what the special rules were.

The rest of the day passed quickly and toward the late afternoon the property room Sergeant brought our personal property and small black and white TVs to us (at the time, death row was not allowed to have color TVs-it wasn’t until 2004 that we were finally allowed to purchase small color TV’s).

As the days and weeks passed, Amos and Bob and I formed a close comradery, constantly passing the time talking and joking. Since it was our first death warrant, none of us were concerned as we knew that nobody was executed on their first death warrant-at least, they weren’t back then. That later changed.

But it wasn’t all fun and our gallows sense of humor only hid the stress we all felt as the reality of possible death hung over us. as well as those closest to us. Especially in the morning hours a heavy silence would hang over the cell block until one of us finally called out to another and asked how we’re doing. If the silence became too prolonged we would check up on each other and use humor to take that edge off.

On the other side of the death watch floor they had Leo Jones and Jeff Daugherty, next in line for scheduled execution. The reality of the uncertainty of our fate was driven home that first week of November when in the early morning hours of November 7, 1988 the Lieutenant came down and woke us up and told us to grab what we need for the day as we were being moved upstairs right away.

They told us that Jeff didn’t get a stay of execution as we all had expected. At that time Florida carried out executions around 7:00 a.m. Grabbing our bedrolls and some writing materials, one by one we were moved upstairs since they didn’t want any prisoners on the death watch floor when they were carrying out an execution. That would also change in later years (please read: “Execution Day- Involuntary Witness to State Sanctioned Murder”).

Each of us was placed in a cell on the second floor and waited the hours out, knowing that downstairs they were putting Jeff to death. Around mid- morning the wing Sergeant told us to grab our property since we were going back downstairs. A short while later the death watch Sergeant came and escorted us, one by one, back downstairs.

Not long after that Bob got a Stay of Execution and was moved back to the regular death row housing area. About a week later Leo Jones came within a few hours of execution, even having his head and lower leg shaved and eating his last meal, before receiving a Stay of Execution and also being moved back to the death row housing wing.

After Leo was moved off death watch, they moved Amos King and me around to the east side. We were now the next in line for scheduled execution did Amos was put in cell three and I was placed in cell one. That same day they moved Abron Scott, John Marek and David Johnston to the west side cells we’d just vacated and we had a full house again.

As our scheduled execution date drew closer, Amos got a stay while I remained alone on death watch. (Please read “The Day God Died” which describes my last few days on death watch). On November 28, 1988 I finally received a 48 hour temporary Stay of Execution and then on December 2, 1988 I received a full Stay of Execution and was moved back to the regular death row wing.

As the years passed, every person I was on death watch with died except me. Of the eight men I shared that experience with, I am the only one still alive.

Leo Jones, Jeffrey Daughtery, John Morek and Amos King all were eventually executed, while my brother Bob died of cancer over a decade later, and David Johnston died of a heart attack when a second death warrant was signed against him in 2010. Myself I would survive another death watch experience. (check out the PBS documentary “Cell One” about my 2016 death watch experience at http://cellone.wlrn.digital/)

|

| Michael Lambrix was executed by the State of Florida on October 5, 2017 |

1 Comment

feministe

April 9, 2018 at 1:33 amAs usual, a good piece from Mike. Would love to see any others he wrote that are not yet posted – I know you guys said you had several unpublished posts he wrote last year, but I think this is the first I've seen so far.